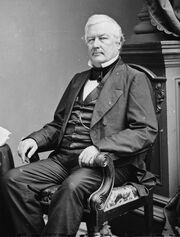

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800 – March 8, 1874) was the 13th President of the United States, serving from 1850 until 1853, and the last member of the Whig Party to hold that office. He was the second Vice President to assume the Presidency upon the death of a sitting President, succeeding Zachary Taylor who died of what is thought to be acute gastroenteritis . Fillmore was never elected President; after serving out Taylor's term, he failed to gain the nomination for the Presidency of the Whigs in the 1852 presidential election, and, four years later, in the 1856 presidential election, he again failed to win election as the Know Nothing Party and Whig candidate.

Early life and career[]

Fillmore was born in a log cabin in Cayuga County in the Finger Lakes region of New York State, to Nathaniel Fillmore and Phoebe Millard, as the second of nine children and the eldest son. (As this was three weeks after George Washington's death, Fillmore was the first U.S. President born after the death of a former president.) Though a Unitarian in later life, Fillmore was descended from Scottish Presbyterians on his father's side and English dissenters on his mother's. His father apprenticed him to a brutal cloth maker in Sparta, New York, at age fourteen to learn the cloth-making trade. He left after four months but subsequently took another apprenticeship in the same trade at New Hope, New York. He struggled to obtain an education under frontier conditions, attending New Hope Academy for six months in 1819. Later that same year, he began to clerk for Judge Walter Wood of Montville, New York, under whom Fillmore began to study law.

Millard Fillmore helped build this house in East Aurora, New York, and lived here 1826-30.

He fell in love with Abigail Powers, whom he met while at New Hope Academy and later married on February 5, 1826 . The couple had two children, Millard Powers Fillmore and Mary Abigail Fillmore. After leaving Wood and buying out his apprenticeship, Fillmore moved to Buffalo, New York, where he continued his studies in the law office of Asa Rice and Joseph Clary. He was admitted to the bar in 1823 and began his law practice in East Aurora. In 1834, he formed a law partnership, Fillmore and Hall (becoming Fillmore, Hall and Haven in 1836), with his good friend Nathan K. Hall (who would later serve in his cabinet as Postmaster General). It would become one of western New York's most prestigious firms.

In 1846, he founded the private University of Buffalo, which today is the public State University of New York at Buffalo (SUNY Buffalo), the largest school in the New York state university system.

His military service was limited. He served in the New York militia during the Mexican War of 1846 and during the American Civil War.

Politics[]

In 1828, Fillmore was elected to the New York State Assembly on the Anti-Masonic ticket, serving for one term, from 1829 to 1831. He was later elected as a Whig (having followed his mentor Thurlow Weed into the party) to the 23rd Congress in 1832, serving from 1833 to 1835. He was re-elected in 1836 to the 25th Congress, to the 26th and to the 27th Congresses serving from 1837 to 1843, declining to be a candidate for re-nomination in 1842. In Congress, he opposed the entrance of Texas as a slave territory. He came in second place in the bid for Speaker of the House of Representatives in 1841. He served as chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee from 1841 to 1843 and was an author of the Tariff of 1842, as well as two other bills that President John Tyler vetoed. After leaving Congress, Fillmore was the unsuccessful Whig candidate for Governor of New York in 1844. He was the first New York State Comptroller elected by general ballot, and was in office from 1848 to 1849. As state comptroller, he revised New York's banking system, making it a model for the future National Banking System.

Vice Presidency 1849–1850[]

Engraving of Vice President Fillmore

At the Whig national convention in 1848, the nomination of Gen. Zachary Taylor for president angered both the supporters of Henry Clay and the opponents of the extension of slavery into the territories gained in the Mexican–American War. A group of practical Whig politicians nominated Fillmore for vice president, believing that he would heal party wounds because he came from a non-slave state even though he was relatively obscure, and because he would help the ticket carry the populous state of New York. Fillmore was also selected in part to block New York state machine boss Thurlow Weed from receiving the vice presidential nomination (and his front man William H. Seward from receiving a position in Taylor's cabinet). Weed ultimately got Seward elected to the senate. This competition between Seward and Fillmore led to Seward's becoming a more vocal part of cabinet meetings and having more of a voice than Fillmore in advising the administration. The battle would continue even after Taylor's death.

Taylor and Fillmore disagreed on the slavery issue in the new western territories taken from Mexico in the Mexican-American War. Taylor wanted the new states to be free states, while Fillmore supported slavery in those states as a means of appeasing the South. In his own words: "God knows that I detest slavery, but it is an existing evil... and we must endure it and give it such protection as is guaranteed by the Constitution." Fillmore presided over the Senate during the months of nerve-wracking debates over the Compromise of 1850. During one debate, Senator Henry S. Foote of Mississippi pulled a pistol on Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri. Fillmore made no public comment on the merits of the compromise proposals, but a few days before President Taylor's death, Fillmore suggested to the president that, should there be a tie vote on Henry Clay's bill, he would vote in favor of the North.

Presidency 1850–1853[]

Offical White House portrait.

Policies[]

Upon the unexpected death of President Taylor on July 9, 1850, Fillmore ascended to the presidency. The change in leadership also signaled an abrupt political shift as Fillmore appointed his own cabinet. Taylor, himself, had been about to replace his entire scandal-ridden cabinet at the time of his death, but now, beginning with the appointment of Daniel Webster as Secretary of State, Fillmore's cabinet would be dominated by individuals who, with the exception of Treasury Secretary Thomas Corwin, favored what would come to be called the Compromise of 1850. As president, Fillmore dealt with increasing party divisions within the Whig party; party harmony became one of his primary objectives. He tried to unite the party by pointing out the differences between the Whigs and the Democrats (by proposing tariff reforms that negatively reflected on the Democratic Party). Another primary objective of Fillmore was to preserve the Union from the intensifying slavery debate. Henry Clay's proposed bill to admit California to the Union still aroused all the violent arguments for and against the extension of slavery without any progress toward settling the major issues (the South continued to threaten secession). Fillmore recognized that Clay's plan was the best way to end the sectional crisis (California free state, harsher fugitive slave law, abolish slave trade in DC). Clay, exhausted, left Washington to recuperate, passing leadership to Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. At this critical juncture, President Fillmore announced his support of the Compromise of 1850. On August 6, 1850, he sent a message to Congress recommending that Texas be paid to abandon its claims to part of New Mexico. This, combined with his mobilization of 750 Federal troops to New Mexico, helped shift a critical number of northern Whigs in Congress away from their insistence upon the Wilmot Proviso—the stipulation that all land gained by the Mexican War must be closed to slavery. Douglas's effective strategy in Congress combined with Fillmore's pressure gave impetus to the Compromise movement. Breaking up Clay's single legislative package, Douglas presented five separate bills to the Senate: Admit California as a free state. Settle the Texas boundary and compensate the state for lost lands.

Later Life and Death[]

A portrait of an older Millard Fillmore.

By September 20, President Fillmore had signed them into law. Webster wrote, "I can now sleep of nights." Whigs on both sides refused to accept the finality of Fillmore's law (which led to more party division, and a loss of numerous elections), which forced Northern Whigs to say "God Save us from Whig Vice Presidents." Fillmore's greatest difficulty with the fugitive slave law was how to enforce it without seeming to show favor towards Southern Whigs. His solution was to appease both northern and southern Whigs by calling for the enforcement of the fugitive slave law in the North, and enforcing in the South a law forbidding involvement in Cuba (for the sole purpose of adding it as a slave state). Another issue that presented itself during Fillmore's presidency was the arrival of Lajos Kossuth (exiled leader of a failed Hungarian revolution). Kossuth wanted the United States to abandon its non-intervention policies when it came to European affairs and recognize Hungary's independence. The problem came with the enormous support Kossuth received from German-American immigrants to the United States (who were essential in the re-election of both Whigs and Democrats). Fillmore refused to change American policy, and decided to remain neutral despite the political implications that neutrality would produce. Fillmore appointed Brigham Young as the first governor of the Utah Territory in 1850. Utah now contains a city and county named after Millard Fillmore. Another important legacy of Fillmore's administration was the sending of Commodore Matthew C. Perry to open Japan to Western trade, though Perry did not reach Japan until Franklin Pierce had replaced Fillmore as president. A less dramatic legacy is that Fillmore, a bookworm, found the White House devoid of books and initiated the White House library.

Fillmore was one of the founders of the University of Buffalo. The school was chartered by an act of the New York State Legislature on May 11, 1846, and at first was only a medical school. Fillmore was the first Chancellor, a position he maintained while both Vice President and President. Upon completing his presidency, Fillmore returned to Buffalo, where he continued to serve as chancellor. After the death of his daughter Mary, Fillmore went abroad. While touring Europe in 1855, Fillmore was offered an honorary Doctor of Civil Law (D.C.L.) degree by the University of Oxford. Fillmore turned down the honor, explaining that he had neither the "literary nor scientific attainment" to justify the degree. He is also quoted as having explained that he "lacked the benefit of a classical education" and could not, therefore, understand the Latin text of the diploma, adding that he believed "no man should accept a degree he cannot read."] By 1856, Fillmore's Whig Party had ceased to exist, having fallen apart due to dissension over the slavery issue, and especially the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Fillmore refused to join the new Republican Party, where many former Whigs, including Abraham Lincoln, had found refuge. Instead, Fillmore joined the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic American Party, the political organ of the Know-Nothing movement. He ran in the election of 1856 as the party's presidential candidate, attempting to win a non-consecutive second term as President (a feat accomplished only once in American politics, by Grover Cleveland). His running mate was Andrew Jackson Donelson, nephew of former president Andrew Jackson. Fillmore and Donelson finished third, carrying only the state of Maryland and its eight electoral votes; but he won 21.6% of the popular vote, one of the best showings ever by a Presidential third-party candidate. On February 10, 1858, after the death of his first wife, Fillmore married Caroline McIntosh, a wealthy widow. Their combined wealth allowed them to purchase a big house in Buffalo, New York. The house became the center of hospitality for visitors, until her health began to decline in the 1860s. Fillmore helped found the Buffalo Historical Society (now the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society) in 1862 and served as its first president. Throughout the Civil War, Fillmore opposed President Lincoln and during Reconstruction supported President Johnson. He commanded the Union Continentals, a corps of home guards of males over the age of 45 from the Upstate New York area. He died at 11:10 p.m. on March 8, 1874, of the after-effects of a stroke. His last words were alleged to be, upon being fed some soup, "the nourishment is palatable." On January 7 each year, a ceremony is held at his grave site in the Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo.

Legacy[]

Some northern Whigs remained irreconcilable, refusing to forgive Fillmore for having signed the Fugitive Slave Act. They helped deprive him of the Presidential nomination in 1852. Within a few years it was apparent that although the Compromise had been intended to settle the slavery controversy, it served rather as an uneasy sectional truce. Robert J. Rayback argues that the appearance of a truce, at first, seemed very real as the country entered a period of prosperity that included the South.[11] Although Fillmore, in retirement, continued to feel that conciliation with the South was necessary and considered that the Republican Party was at least partly responsible for the subsequent disunion, he was an outspoken critic of secession and was also critical of President Buchanan for not immediately taking military action when South Carolina seceded. Benson Lee Grayson suggests that the skillful avoidance of potential problems by the Fillmore administration is too often overlooked. Fillmore's constant attention to Mexico avoided a resumption of the hostilities that had only broken off in 1848 and laid the groundwork for the Gadsen Treaty during Pierce's administration Meanwhile, the Fillmore administration ironed out a serious dispute with Portugal left over from the Taylor administration, smoothed over a disagreement with Peru, and then peacefully resolved other disputes with England, France, and Spain over Cuba. At the height of this crisis, the Royal Navy had fired on an American ship while at the same time 160 Americans were being held captive in Spain. Fillmore and his State Department were able to resolve these crises without the United States going to war or losing face. Because the Whig party was so deeply divided, and the two leading national figures in the Whig party (Fillmore and his own Secretary of State, Daniel Webster) refused to combine to secure the nomination, Winfield Scott received it. Because both the north and the south refused to unite behind Scott, he won only 4 of 31 states, and lost the election to Franklin Pierce. After Fillmore's defeat the Whig party continued its downward spiral with further party division coming at the hands of the Kansas Nebraska Act, and the emergence of the Know Nothing party. Most of his correspondence was destroyed in pursuance of a direction in his son's will